Recognising Indigenous Epistemologies

Unique LIAS conference brings together Indigenous and museum representatives for the first time for research discussions

2025-05-02 The LIAS intervention “Beyond Restitution: Indigenous Practices, Museum, and Heritage” brought together representatives of indigenous communities from Latin America and museum curators for the first time to discuss indigenous perspectives on cultural heritage, museum collecting practices and the restitution of cultural artefacts. The aim was to broaden discussions on the restitution of cultural heritage and to engage in a differentiated academic debate on indigenous knowledge practices, the significance of artefacts and their relationships to regions, landscapes and communities.

During the welcome and opening by Susanne Leeb, Co-Director of LIAS, Fernanda Pitta, Professor of the Art, Theory and Criticism Research Unit of the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo and Principal Investigator in the research project “Decay Without Mourning: Future Thinking Heritage Practices” and Bruno Moreschi, LIAS Fellow and research associate in the research project “Decay Without Mourning: Future Thinking Heritage Practices”, Pitta emphasised that restitution is only one part of a broader debate on cultural heritage, which must be understood as a dynamic practice. She emphasised that decay must be understood as a creative and transformative process that is itself part of the heritage narrative. LIAS Fellow Bruno Moreschi addressed how their projects related to ”Decay Without Mourning: Future Thinking and Hertitage Practices” explore how technological processes work in different contexts, including indigenous communities. He pointed out that indigenous objects are not only artefacts, but also tools with specific functions and meanings.

In her presentation, moderated by Fernanda Pitta, Francy Baniwa, Brazilian anthropologist, researcher and artist, Içana River, Amazonas, criticised the role of museums in the representation of indigenous objects, which for her are a living library and a reservoir of knowledge. They are often only recognised by general information such as size and continent of origin, without understanding their cultural significance. Their community has therefore built up its own collection to reinterpret the museum artefacts from an indigenous perspective. A central concern of her work is to recognise this knowledge as a science that is passed on within the community - especially by women. She also called for collaboration with researchers to be shaped as an equal dialogue by actively involving indigenous researchers in the research process. Only then could it be said that museum studies could move away from Western perspectives and respect the current material and immaterial, social and collective meanings of the objects from the perspective of the communities of origin.

The Brazilian artist Glicéria Tupinambá, who represented her home country at the Venice Biennale last year, also rejected the term ‘objects’ in her presentation, which was moderated by Bruno Moreschi, and instead spoke of ‘ancestors’. “When I am in a museum, I feel a ‘cosmic agony’,” said Tupinambá. “How can I communicate with these objects and translate them for visitors?” Her artistic and scientific approach aims to make the manufacturing processes of the objects visible as central components of their cultural value, because she sees ‘signatures’ of the makers, who are often women, in the materials used, the manufacturing tools and in the objects themselves. Tupinambá also came to the conclusion that a new museum practice is needed that emphasises the biographical and ritual dimensions of objects. She called on Western museums to give indigenous researchers the space to realise their continuous transmission of knowledge and spiritual connections with the objects from their own perspective.

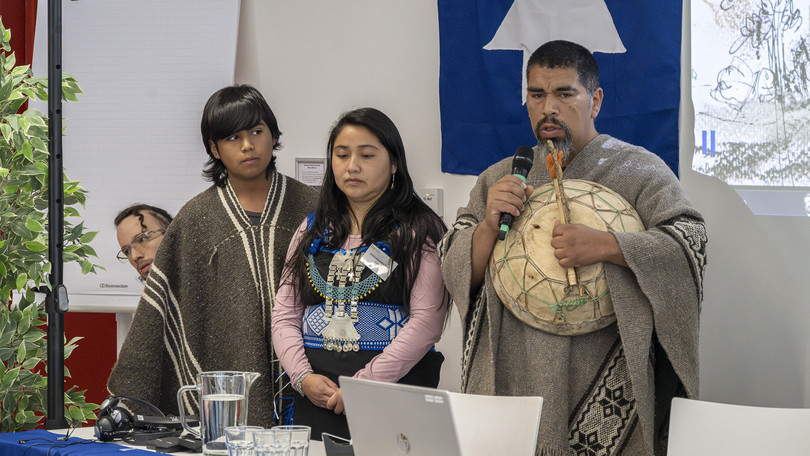

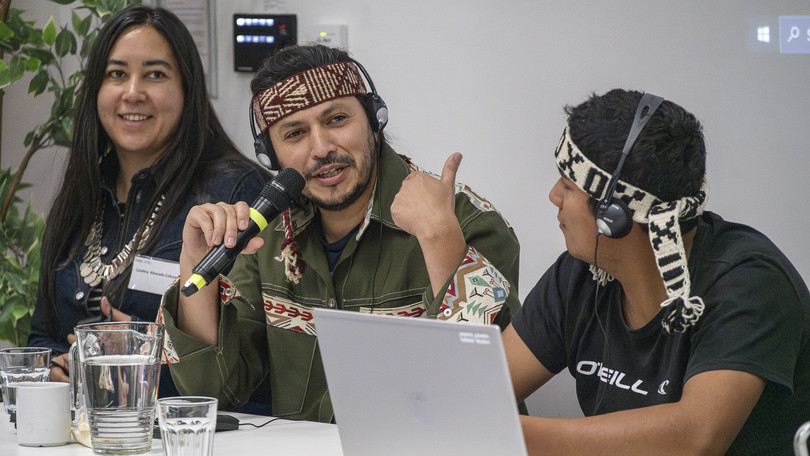

Sebastián Eduardo Dávila, research associate at Leuphana, introduced Mapuche filmmaker Francisco Huichaqueo and a group of indigenous artists and scientists. The group had already seen objects from their Mapuche culture at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. “I have no words to describe this encounter,” said Huichaqueo, “perhaps out of anger.” He spoke about the “epistemic theft” of the objects that goes hand in hand with the appropriation of indigenous cultural artefacts. Western conservation concepts destroy the living connection between the objects and their communities of origin: “What are they preserving and what are we preserving? The objects are for us, they have a spirit, and they still exist with all their traumas.” Huichaqeo thus addressed ongoing colonial upheavals that are evident in the objects, which for her are not objects, but spiritual and cultural connecting elements with their own agency. Resistance to Western practices manifests itself, among other things, in the demand for curatorial autonomy for indigenous researchers and artists. This has political dimensions: Because even if the artefacts were to return to Chile - a necessary step, as they are the basis of their ecosystem - the Mapuche would not necessarily preserve them, as the Chilean state is hardly interested in them.

Laura Sabel, Research Assistant at the DFG Research Training Group ‘Cultures of Critique’ at Leuphana introduced Mama José Shibulata Zarabata Sauna and José Manuel Sauna Mamatacan, representatives of the Kággaba from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. The Group argued that the return of objects is inextricably linked to territorial sovereignty. Indigenous objects are forms of life that must operate in their contexts of origin to fulfil their social function: ‘It is a question of life and death,’ said the dignitary Mama José Shibulata Zarabeta Sauna. “Authority does not begin with us, but with the objects. That's why we call it a sacred place. Everything is connected. When we reclaim them, we are defending forests, rivers, mountains. The objects must be where they belong. They must be reintegrated into their sacred place of origin, because they will eventually say something.” The Kággaba therefore see restitution efforts as a lifelong task that is linked to the healing of communities and the restoration of indigenous knowledge systems. This is justified not least by the thousands of years of knowledge that he and his community have made available to Western museums and societies.

Common perspectives were developed in the final discussion. However, current limits to the realisation of demands were also addressed, not least in questions of ownership and affiliation, the different significance of cultural assets and ways of dealing with them, and in bureaucratic and legal obstacles. For many, some of whom were in Europe for the first time, the fundamental question arose as to what the value of the objects in a European culture actually is. After all, very few people living here have a living connection to them; they are not part of their knowledge and ancestral culture, their cosmologies, their ecosystem and territory and their social relationships, which are established via the objects. All participants agreed that the appropriation of most objects must be recognised as an act of violence. Therefore, museums that are aware of their colonial past should actively work together with the communities of origin, with representatives of the indigenous communities claiming decision-making authority. Furthermore, indigenous curators and researchers should be involved in decision-making processes and ensure the correct categorisation of objects and different archiving and presentation practices. This is only a first step on the way to a decolonisation of knowledge that recognises indigenous epistemologies and languages in scientific and museum institutions. All experts recognise that restitution is an open, long-term process in which the return of objects is not the end, but part of the ongoing renegotiation of relationships between museums and indigenous communities. After all, restitution is much more than the return of artefacts. It became clear more than once that it is primarily about restoring a destroyed relationship and balance.