LIAS Lecture Grace Musila: “African Literature and Liberation Struggle Movements”

On freedom, violence, and memory in African literature

2025-11-05

Kenyan literary scholar Grace Musila, Professor of African Literature at the University of Johannesburg and LIAS Senior Fellow, devoted her lecture on 28 October to an urgent and complex question: How do African literatures tell the story of liberation – and what do they reveal about the tensions between the ideals of decolonization and the contradictory realities of postcolonial societies?

In her lecture, Musila highlighted her approach to literary analysis and cultural-historical reflection based on political theory so as to examine more closely those “archives of refusal” in which African writers negotiate alternative ideas of freedom and the future. Musila observed that the euphoric narrative of the end of colonialism – exemplified in the South African film Jerusalema – Gangster’s Paradise – often stands in sharp contrast to the experience of continued inequality and violence.

Central to Musila’s argument is the concept of “tidalectics” – a concept inspired by Caribbean thinker Kamau Brathwaite that describes cyclical, wavelike processes of liberation and setbacks. According to Musila, African literature constantly oscillates between hope and disillusionment, between the utopian aspiration of independence and the disillusionment caused by its incomplete realization.

In her lecture, Musila situated works such as Chinua Achebe’s Anthills of the Savannah within this tension. In the novel, the parable of a turtle confronting a leopard serves as a metaphor for the struggle for equality and interpretive authority. Literature, according to Musila, acts like the turtle here: It creates spaces of resistance.

Violence, Spirituality, and Gender in Resistance

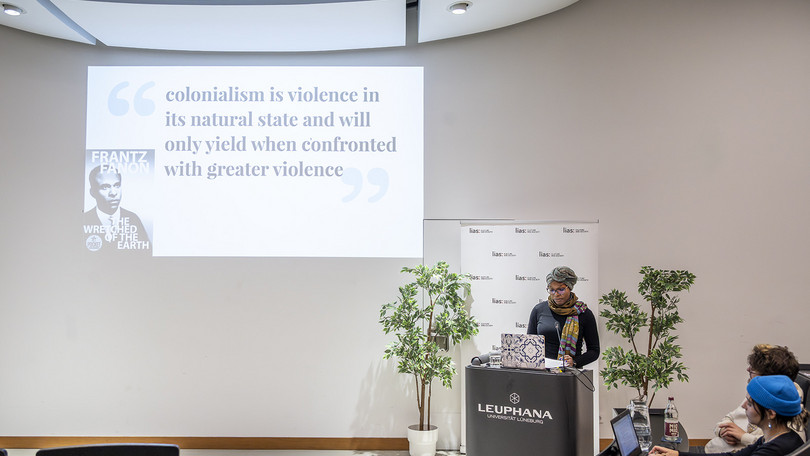

Musila reminded her audience that colonialism was always a system of violence which, as Frantz Fanon (1925–1961) emphasized, could only be broken by greater violence. At the same time, she pointed to the spiritual dimension of many anticolonial movements, in which prophets and healers played a leading role. Their visions – bullets turning into water, white colonizers returning to the sea – show that resistance was also fuelled by a cosmological-ethical understanding of the world.

In this context, Grace Musila discussed the gender dimension of the anticolonial struggle. Authors such as Yvonne Vera (The Stone Virgins) and Maaza Mengiste (The Shadow King) expose not only the violence of colonialism, but also the sexism within liberation movements. According to Musila, women were caught “between two patriarchies” – the European and the African. Their experiences of exploitation and sexualized violence rarely found their way into the official narratives of liberation.

A recurring theme in liberation movements was the instrumentalization of art. In the tradition of Ngũgĩ waThiong’o or Ousmane Sembène, literature was understood as a weapon – as a means of resistance. However, Musila is critical: “This instrumentalization threatens to cannibalizehuman complexity in the artwork. By serving moral binaries, liberation art often loses sight of the ambivalence, betrayal,and inner turmoil of those fighting,” says the literary scholar.

The motif of the “collaborator”, the self-loathing Black person who fights on the side of the colonizers, is a particularly revealing example. Works such as Vyasna Perpétua’s Mayombe or Vera’s The Stone Virgins paint a grim picture of the aftermath of armed resistance, in which violence and trauma live on.

In the ensuing discussion, Musila explored the question of archives of liberation – those fragile spaces of memory that are perpetuated through literature, art, and oral narratives. Works of art, she argues, function as counter-archives that fill the gaps in state and colonial historiography.

The discussion of generational relations in South African protest movements was particularly stimulating: Young activists accuse the older generation of betraying the ideals of the struggle, while the older generation, in turn, perceives the impatience of youth as ingratitude. Musila interprets these conflicts as a continuation of the “intergenerational struggles”already described by Frantz Fanon.

Utopias and Residues of Hope

Despite all the disillusionment, Musila insists that “residues of hope” persist in African literature. Utopian visions – however fragile and broken they may seem – are essential for keeping alternative futures conceivable. “Poetic licence” offers a creative freedom that allows history to be not only documented but also reappropriated.

Grace Musila’s lecture was a plea for the ethical and aesthetic complexity of African literature. It shows that liberation should not be understood as a completed episode, but as an ongoing process – as a tidal wave of hope, betrayal, memory,and reinvention. African writers, according to Musila, are both chroniclers and architects of this movement: They keep the contradictions of the struggle for independence open and preserve the possibility that history – like the turtle in Achebe’s parable – can be retold in a different way.