Understanding gaze is universal across cultures

2026-02-10 Lüneburg/Leipzig. Recognizing where other people are looking and what they are focusing their attention on is one of the most fundamental skills of human communication. A new international study led by Leuphana University Lüneburg and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig now provides clear evidence that this ability is based on the same cognitive mechanisms across cultures.

The freely accessible study, published in the journal Child Development, shows that even when children grow up in very different cultural contexts, they process eye contact information from others in the same fundamental way.

Until now, many assumptions about basic patterns of social cognition have often been based on small samples from Western, affluent, and urban populations. The new study significantly broadens this perspective. More than 1,300 children between the ages of three and ten from 17 communities in 14 countries across five continents were examined.

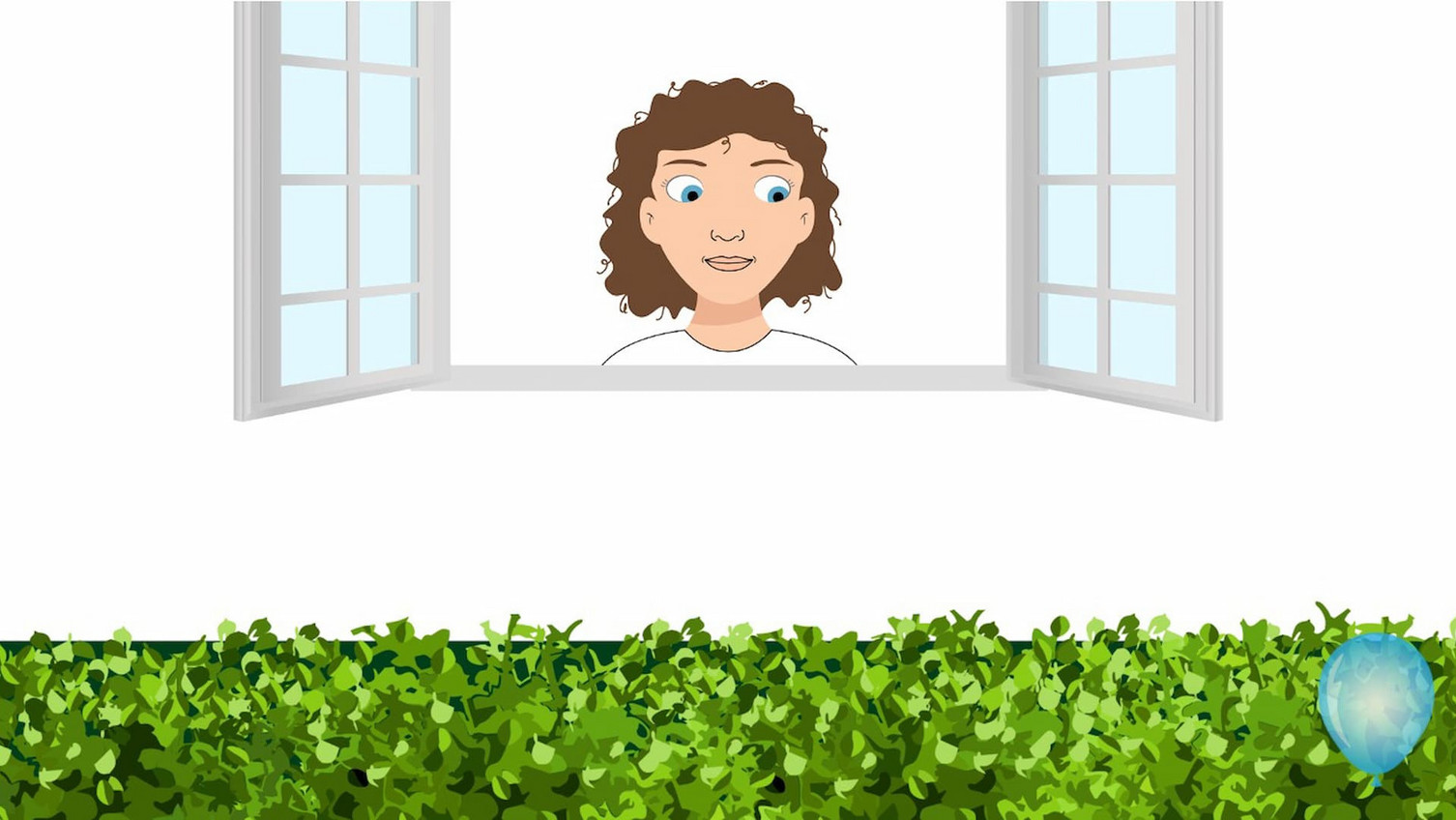

In the experiment, the children played a tablet-based game: On the screen, a balloon flew behind a hedge. A character tracked the balloon's flight solely with their eyes. The children were then asked to touch the spot on the hedge where they thought the balloon would land—based only on the character's gaze direction. The researchers measured how accurately the children hit the balloon's actual landing point.

In addition, the international research team used a computer-based model that describes gaze tracking as a form of mental "direction estimation": According to this model, children infer a social gaze direction from the eye movements of others.

The results paint a clear picture: While children and communities differed in how precisely they followed gazes, the same fundamental cognitive processing structure was evident in all the cultures studied.

"Across all 17 communities, we see precisely the processing signature that our model predicts. This strongly suggests that gaze processing is based on a common cognitive mechanism," explains Manuel Bohn, Professor of Developmental Psychology at Leuphana University Lüneburg and lead author of the study. Manuel Bohn was a Senior Scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology until 2023 and continues to work there as a visiting researcher.

Individual differences were primarily explained by methodological factors—especially the children's familiarity with tablet computers. In all the communities studied, older children performed better on average than younger children.

To ensure fair and comparable measurements across different cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic contexts, the researchers, together with local partners, adapted all visual and auditory elements of the task to the specific circumstances. “This study demonstrates what successful international collaboration in developmental psychology research can look like,” says Roman Stengelin from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, also a lead author.

The full study is available here: https://academic.oup.com/chidev/advance-article/doi/10.1093/chidev/aacaf017/8439672